KUSHANA BUSH

KUSHANA BUSH

in conversation with Melissa Keys

Name: Kushana Bush

Date of birth: 09 June 1983

Place of birth: Ōtepoti/Dunedin, New Zealand

Occupation: Artist

MK: Time registers in your exquisite compositions: in their multifarious richness and throughout the viewer’s process of absorbing their intricate complexity. I’m interested to hear your thoughts on the passage of time in your work.

KB: My paintings are created slowly; they refer to the past and tell of the here and now. Yet by the time an image is complete, it’s as much of a stranger to me as the back of my head. With regularity, I unearth things in pictures I’ve made that I can’t recall painting. The best way to describe that phenomenon is to liken the making of a miniature to taking a long walk over a mountain; you can’t possibly remember every single pebble you saw along the way.

Some of the paintings I made back in 2016 were of jamborees, street parades and festivals, but in 2020 – year of the pandemic – I look at that same throng of painted bodies within the moist breath zone and I’m filled with quiet horror. Paintings by their very nature are static objects, and yet time warps and bends their translation.

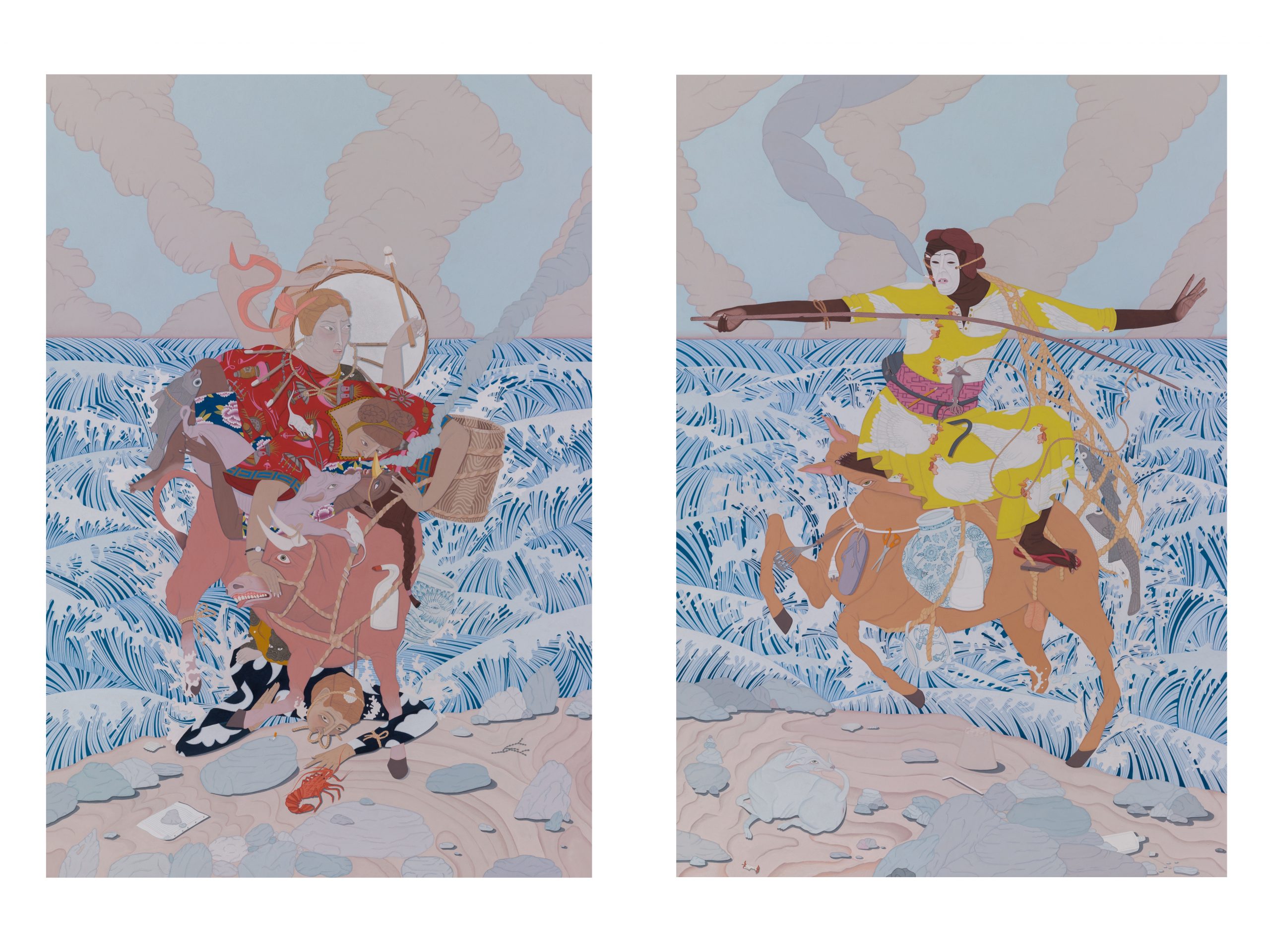

Time also adds or subtracts meaning. My home of Ōtepoti/Dunedin is an area once populated by prospectors who flocked to the region during the 19th-century gold rush, and even today you could still potentially dig up a Chinese ginger jar. These vessels were the ceramic equivalent of our modern-day tin can or chip packet, only discarded in the 1860s. In 2020, these hand-built, hand-painted objects are revered; however, disconcertingly, the reverse is also true – in the same city, old churches have been converted into student nightclubs. Time transforms the humdrum into the sacred and the sacred into the humdrum. What our culture values, or doesn’t value, says a lot about the exact moment we are living in.

MK: A profusion of traditions and references are layered and synthesised in your pictures. These include Japanese Ukiyo-e prints and Mughal and Persian miniatures alongside Western, Gothic, Renaissance and modern art. The work of artists such as Katsushika Hokusai, Hieronymus Bosch, Paula Rego, Piero della Francesca, George Grosz, Otto Dix and Stanley Spencer, among others, also come to mind. What are you drawn to at the moment?

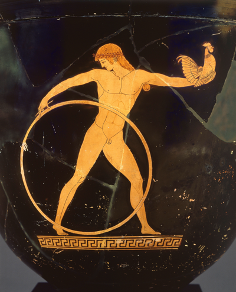

Detail of Red-figure bell krater with Zeus and Ganymede (c. 500–490 BC), Greek, Attic, attributed to the Berlin Painter. Musée du Louvre, Paris; © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Stéphane Maréchalle

KB: I don’t know if it has quite wormed its way into my own work yet, but I’m currently lusting over a man who’s been dead for more than 2000 years, known as the Berlin Painter. If he were alive today, I would hide in his workshop and spy on him as he performed the most intimate of actions: holding a pot in one hand and fluently curling an image around it with the other.

Some Greek vase painters have been given wonderfully descriptive names by scholarly connoisseurs, such as the Affecter, the intriguingly named Elbows Out and, what I might have been named for all the wrong reasons, the Pig Painter. But I can’t even think of consuming the contents of the vessels when I look at pots by the Berlin Painter; he evokes in me both scorching envy and reassuring calm.

I managed to spot his handiwork among an ocean of Attic pottery at the British Museum. You might recognise his style yourself if I renamed him the Negative Space Commander. Find me a line drawn with more conviction. His confident lines are as graceful, electric and kinetic as a seagull flying at full speed towards your face before artfully arching upwards without grazing a single hair on your chin.

I find this kind of falling in love with the dead very beneficial; it gives me a great deal to strive for. Give me a tenth of the Berlin Painter’s sureness-of-line and a tenth of his ability to compose positive and negative space and I will die a happy woman.

MK: So, could the concentration, attentiveness and sense of beauty you apply to creating images, even when they often appear to suggest moments of violence or chaos, be construed as ways of making or finding sense in the contemporary world?

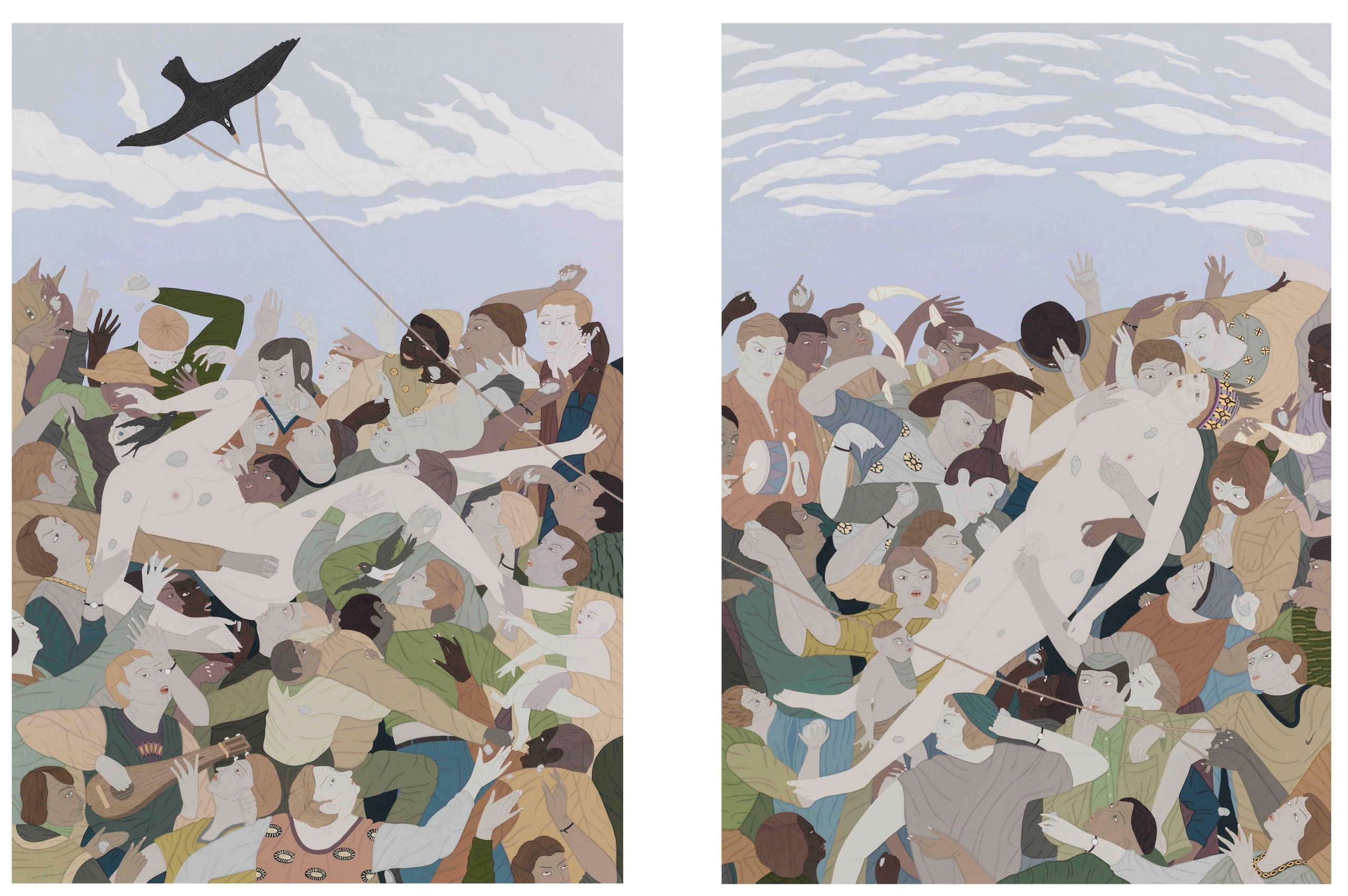

KB: There is an element to what I do that is just play-acting, trying things on for size. In a painting like The stoning diptych, I wanted to embody the vicious actors. Violence is a dormant force in a lot of my work. My painted world is a kind of impossible command to arrest the world in motion; this way, I’m not left cowering – I’m the one staring it down. There’s solace in painting fingernail by fingernail, tooth by snarling tooth; it’s an attempt to grasp the ungraspable, however futile that quest might seem.

But how beauty enters the equation, I don’t quite know … I’ve always had a real hunger for the ideal image that’s just out of reach, and this ache never wanes.

Without images, I would feel shipwrecked on Earth. I use images to map my way through the world; they’re a way of comprehending.

MK: Ultimately enigmatic, fragments and suggestions of stories jostle in your paintings, never quite forming unbroken narratives. How does your practice relate to the tradition of storytelling?

KB: The great minimal abstract expressionist Agnes Martin stated that ‘the value of art is in the observer’. That’s true even for a figurative painter; the artist cannot preach forevermore beside an artwork. It’s vital for a work’s tendrils to stray away from the tight grip of the composer, the playwright and the artist. Over many years, a story is best if it stretches all out of shape and grows into something beautifully corrupted.

MK: Cycles and rituals of life, death, suffering and ecstasy unfold in the worlds you conjure. What do you hope an encounter with your work might offer?

KB: Trying to answer that question feels like staring straight into the Sun. So, instead, I will describe an encounter I had at a fishmonger’s with a dead octopus. What a truly otherworldly creature. Is it purple? Is it white? Or am I trying to describe an absence of colour? How curious its form appears all-folded-up and out-of-the-sea, and how fascinating it is that something can be dead, sad and profoundly beautiful all at the same time.

In July last year, I had that same feeling at the National Gallery, London. I was standing in front of a painting of two views of a crab, depicted from above and below. With striking immediacy, Van Gogh’s modest yet masterful oil painting spoke to me in a language that wasn’t verbal. In an instant, I felt confused, on fire and totally alive.

Kushana Bush is represented by Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney.

kushanabush.com

Darren Knight Gallery

Art Gallery NSW collection

NGV Collection

QAGOMA Collection

Art Gallery NSW Interview

The Pantograph Punch Interview

Image captions

1. Kushana Bush, Plumes, arrows 2015, gouache, metallic paint and pencil on paper, 50.5 × 70 cm, Collection of National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

2. Kushana Bush, The stoning diptych 2015, gouache, metallic paint and pencil on paper, 59 × 42 cm (each image), 90.6 × 122.2 cm (overall, framed), Collection of National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

3. Kushana Bush, Us lucky observers 2016 (detail), gouache, metallic paint and pencil on paper, 75 × 125 cm, Collection of Dunedin Public Art Gallery

4. Kushana Bush, Hark 2018 (detail), gouache, metallic paint and pencil on paper, 55 × 68 cm, Collection of the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane

5. Kushana Bush, Cat’s cradle 2019, gouache and watercolour on paper, 19 × 27 cm, Private collection, Sydney

6. Kushana Bush, Mad bull 2019, gouache and watercolour on paper, 62.3 x 43 cm, Private collection, London

7. Kushana Bush, The small mask 2019, gouache and watercolour on paper, 62.3 x 43 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Brett McDowell Gallery, Dunedin