SHREYAS KARLE

SHREYAS KARLE

In conversation with Melissa Keys

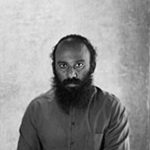

Name: Shreyas Karle

Date of birth: 1 August 1981

Place of birth: Bombay (Mumbai), India

Occupation: Artist

MK: Often assembled from rudimentary found, made and reformed objects and materials alongside drawings, prints, videos and poems, your suggestive and yet enigmatic works are variously witty, fantastical and perplexing. What is the role of humour and the absurd in your practice?

SK: I believe the ‘function of art’ in society has always been unclear. If one tries to make sense of the ‘artistic practice’, one finds that it does not adhere to any logic (as opposed to that of a medical practitioner, legal practitioner, etc.). In fact, it benefits from certain manipulative tendencies and its infinite absurdness. If we try to understand the universe the way it’s been taught to us, we are not able to imagine the farthest bodies and their actions, that either govern the attitudes of time or are governed by time itself. We have to present ourselves as non-intellectual beings whose absurd claims seem humorous to begin with but as these shift into a distant (future) reality, their absurdness will be considered as rational as any philosophical, anthropological or psychological inquiry.

The purpose of art-making is never a proposition of the present or the past, neither is it of the future. It dwells in a certain timelessness and lightlessness (a state where light is present but its source is absent), only to be understood not in itself, but outside of it.

Those who painstakingly try to explain the social, political, cultural or geological through their practices are bringing logic to the absurdness of this incredible language (art language). These practices are interested in presenting art as a representational medium and not as an independent language. As a ‘practitioner’, I am slowly being unaffected by what the language represents and am getting curious about the language itself. In a Benjaminish way, I prefer translation as an independent form to what it translates. Then the absurdness of something in translation can be identified with the language it’s translated from and the language it’s translated to. In addition, this ropes in the translator as a third marker between the two languages. Here the idea of ‘translation’ allows one a bird’s-eye view of the plot – a perfect schema. Only if one is able to stare at the endless sky as a fool can one think of floating and not flying.

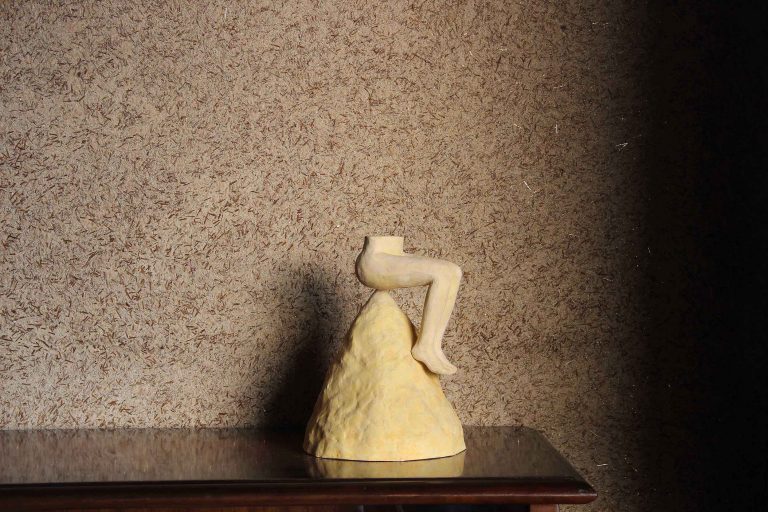

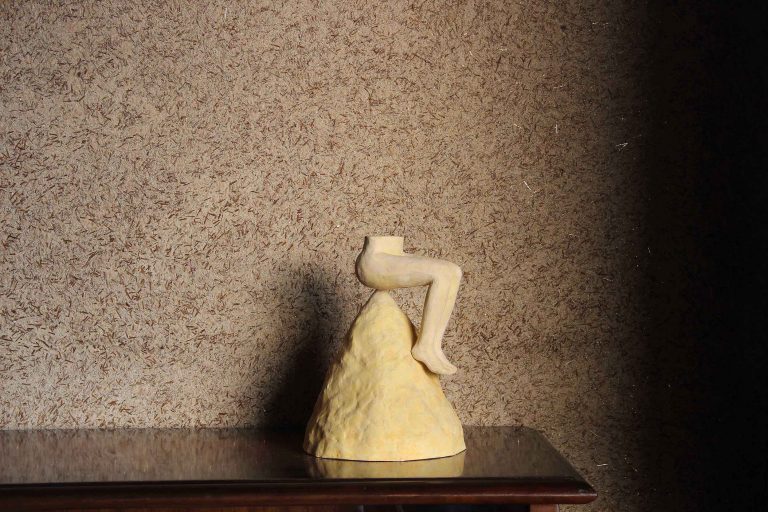

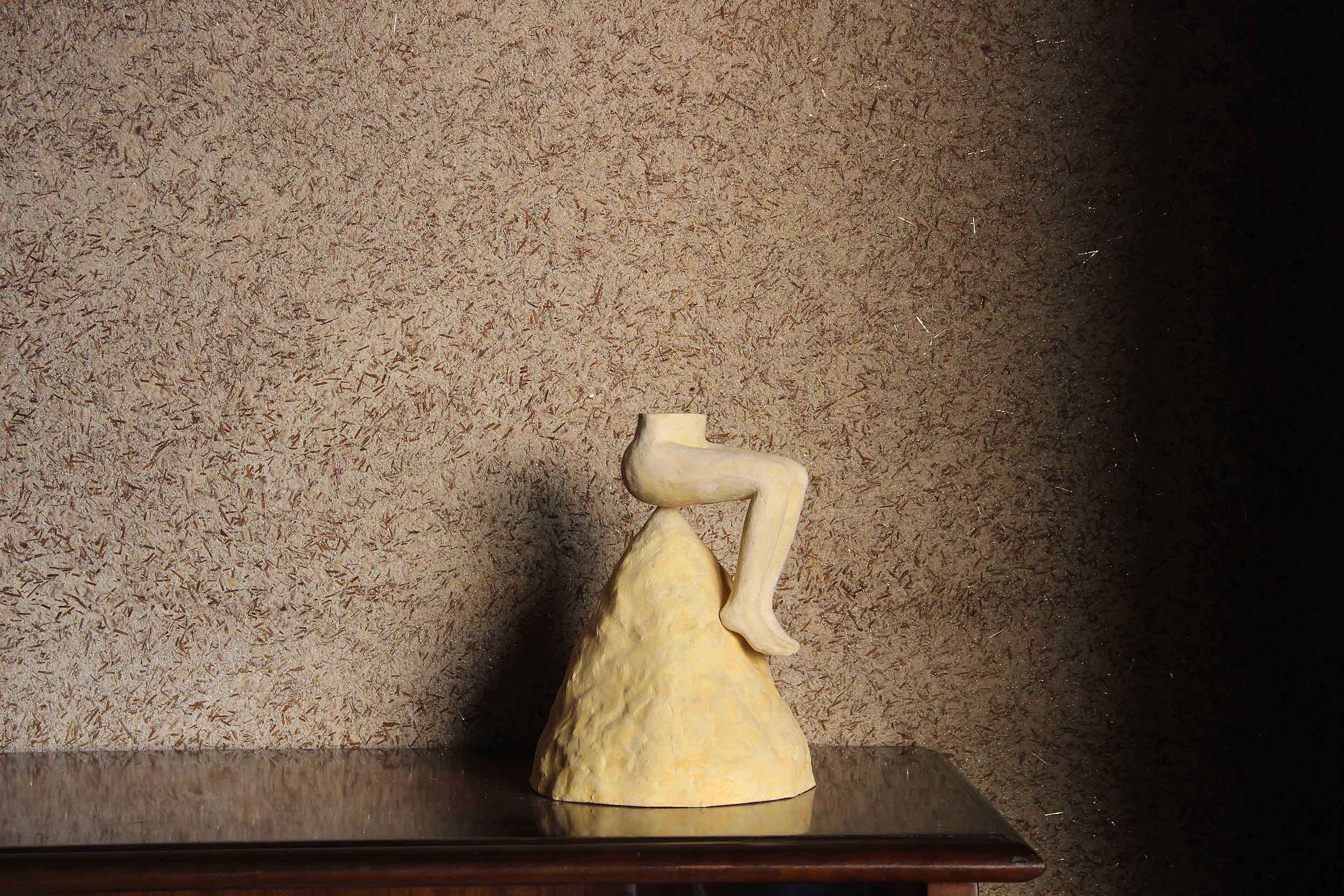

MK: Your installations intermingle diverse cultural and art historical references with mundane domestic forms, settings and actions. For example, your small sculpture Montaigne’s El Caganer in Tanizaki’s toilet alludes to the El Caganer, a traditional figurine of a defecating man that is often found in Catalonian nativity scenes, along with Japanese writer Junichiro Tanizaki’s interest in aesthetics of imperfection, shadows and toilets as liminal spaces. In another work, a large roll of faintly lined fabric amusingly stands in as a Sol LeWitt readymade. Your works subtly play with, complicate and manipulate historical and everyday hierarchies of art, culture, ideas and lived experience. Can you briefly speak about this?

SK: On visiting the Maison La Roche in Paris (designed by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret), one notices a small strip on the wall that reveals its previous painted surfaces. The strip is an accumulation of layers: historical, spatial and socio-economic. It is a strip flattened by time, space and site specificity.

The title of a work is not the work itself. Montaigne’s El Caganer in Tanizaki’s toilet responded to its site – a room with its only window facing a castle (Tokugawa clan). My project was a response to an early Japanese modernist building, initially used as a gas station and a family home. The interiors of the space were designed in a traditional Japanese style with tatami mats and sand-plastered walls. The plaster object (the sitting man) mimicked the changing rulers of the castle it faced through the building’s window. These passages from Montaigne’s essay ‘Of Experience’ visually identify with the caganer: ‘To learn that we have said or done a stupid thing is nothing, we must learn a more ample and important lesson: that we are but blockheads … On the highest throne in the world, we are seated, still, upon our arses.’ And, lest we forget: ‘Kings and philosophers shit, and so do ladies.’1 In Montaigne’s work, the caganer’s excreted matter turns into a seat (throne) that comforts the defecator. This comfort Tanizaki would describe as a pleasurable experience in the context of a Japanese toilet: ‘Here, I suspect, is where haiku poets over the ages have come by a great many of their ideas.’2

The above-mentioned historical and philosophical mashup further lends itself to a composition long reputed to have been by Mozart, a canon in B-flat major entitled Leck mir den Arsch fein recht schön sauber (‘Lick my arse right well and clean’). The mundane act of defecation brings in the political and the poetical simultaneously, while the medium of the work itself (dental plaster) ironically speaks about its association with oral hygiene. This medium acts as a substitute for the absent upper body by becoming a metaphorical mouth as well as a physical anus.

I was once asked to make one of Sol LeWitt’s works following his instructions. I gladly obeyed but improvised. If one were part of the LeWitt fan club, how would one respond to his works? How would one imitate LeWitt’s ideas but not copy them? 77 meters of cloth is a translation of LeWitt’s work. It’s like following a cookbook recipe; one follows the instructions but does not prepare the same dish. There are many factors that would alter the taste and the texture of dishes made by two cooks following the exact same recipe. 77 meters of cloth begins with the act of wrapping cloth around a wooden square cuboid, which is wrapped until it becomes circular.

MK: In an interview in 2016, you commented that ‘instead of being a rebel, one should work in the voids the system has created. It’s impossible to suddenly change a system that has been built up through the long, narrow passage of history. What we can do is add layers to the system.’ How are these additional layers made manifest in your work?

SK: This explanation was provided while speaking about the CONA Foundation, the foundation that my wife/fellow artist, Hemali Bhuta, and I run. It is situated in the suburbs of Bombay (Mumbai). The pedagogical and critical nature of the programming at the foundation resonates with our practices. The manifestation of layers happens through the aspect of solo exhibition-making in institutional spaces. The exhibitions become tools for the dissemination of ideas that contradict the role of the artist as a protagonist. The exhibitions de-pedestalise the works, thus allowing them to unmute themselves, misbehave and subvert notions of permanency, privacy, monumentality and artificial value systems.

Exit Through the Entrance, a 2019 exhibition at Grey Noise, Dubai, manifested the above notions in the form of its visual, material and conceptual experience. All the works for the show (which also included the posters and publications we have produced at the foundation) were designed to be shipped in one crate. The display was created through the act of laying the works on the ground after the opening of the crate.

MK: Your installations have sometimes taken the form of quasi-museological, popular cultural, sociological or archaeological displays. I am interested to hear your thoughts about the relationship between art, artists and the museum.

SK: The institution creates a system of value for both the art and the artist. When a practitioner (while working) does not rely on the external value systems and decides to exist in an alternative value system, they not only create a friction with the institutional premise but also fictionalise the nature of their practice.

Given the nature of established systems, the relationship between the art, artists and institutions is not complex at all. All three sectors behave in an undisruptive manner, with periodic shifts. A certain sense of academia revolves around the three systems, which is representational of classroom dynamics – between the teacher, the student and the subject. The teacher (in this case the ‘institution’) teaches the subject (in this case ‘art’) to the student (in this case the ‘artist’). The student will only score well (get validated) if the subject is well learnt and if there are no inquiries from the student into the nature of the subject. The subject has to be accepted the way it has been conceived and taught.

In contrast to the above example, if the three factors resemble a game of chance (three cups and a ball), each one is symbolic of a cup, and one of the cups hides the ball. The game allows the audience to be an omnipresent factor, without which the game would become valueless. Even if two cups are lying, one of them always contains the truth (hides the truth?). Though the ball here provides the validation of the cup, it allows an equal chance to all three cups to be judged and looked at, democratising the absurdity of the play.

1. Michel de Montaigne, ‘Of Experience’, cited in ‘Michel de Montaigne’, The School of Life, https://www.theschooloflife.com/thebookoflife/the-great-philosophers-michel-de-montaigne/

2. Junichiro Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, cited in Justin Vicari, Japanese Film and the Floating Mind, McFarland & Co., Jefferson, NC, 2016, p. 125.

Shreyas Karle is represented by Project 88, Bombay (Mumbai) and Grey Noise, Dubai.

Project 88

Grey Noise

New Museum’s Generational Triennial

Art Forum

Aichi Triennale 2016 Interview

Aichi Triennale

Cona Foundation

Shreyas Karle, Umer Butt and Aveek Sen discuss Domestic Animals, Art Basel 2020, Grey Noise, Dubai

Places between viewing room, Grey Noise, Dubai

Image captions

1. Portrait photograph by Apoorva Guptye

2. Shreyas Karle, Montaigne’s El Caganer in Tanizaki’s toilet 2016, dental plaster, 22 x 19 cm (diam.)

3. Shreyas Karle, 77 meters of cloth for Sol LeWitt 2016, cotton cloth (77 m) and wood, 90 x 42 cm (diam.)

4. Shreyas Karle, Performing under pressure in the museum of broken objects 2018, museum glass, broken terracotta horse and wooden stand, 50.8 x 68.58 x 7.62 cm

5. Shreyas Karle, Exit Through the Entrance 2019, installation view (gallery island), Grey Noise, Dubai

6. Shreyas Karle, Vaastusangrhalay Ki Dukan (Museum-shop of fetish objects) 2015, installation view, First Look, Asian Art Museum, San Francisco