CHRISTIAN CAPURRO

CHRISTIAN CAPURRO

in conversation with Melissa Keys

Name: Christian Capurro

Date of birth: 1968

Place of birth: Dampier, Australia

Occupation: artist & photographer

MK: Your practice encompasses photography, filmmaking and a range of intensive manual and digital processes. You have described your work as being ‘in pursuit of very particular images’. Can you please elaborate on this?

CC: Thinking about that now, it is less the ‘particular image’ that I’m pursuing than a certain agitation of and about the image. Since, in my view, images themselves are nothing but wood for the fire – whoever’s images they are – the questions that I return to throughout my work deal with the disturbances in us, and in the social field, that mark our encounters with images alone or en masse.

I see the Another Misspent Portrait of Etienne de Silhouette (1999–2015+) project,* in its tensions and with its multiplicities, as something of a figuring or reckoning ‘machine’ that attempts such a pursuit in different registers across economic, temporal, material and aesthetic spheres. *(This was a mass collaborative magazine erasure and (re)inscription work with an associated, and ongoing, ‘response’ program.)

The multi-channel video installation SLAVE, which was shown at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in 2014, approached this agitation and its reverberations in a different way. In that show of eight choreographed Dan Flavin “monument” for V. Tatlin doppelgangers, what mattered most was the tremor of contact both between those luminous bodies and with ours in the space of infidelity that everyday technologies of mediation now openly cultivate. My concern in SLAVE was never with the Flavins in and of themselves; it was only with their stress points as material, pictorial and semantic things.

MK: Always in a state of mistranslation, perpetual reproduction and erasure, your work is fugitive. Curator Francesco Stocchi identifies something alchemical in your process and has memorably suggested that you ‘bring form into a state of impalpability’. You appear to be constantly reworking and remaking. When is a body of work finished for you, if ever?

CC: Apart from the drastic refashioning of a number of the late 1990s and early 2000s Gorgonia correction-fluid works on paper in the decade after they were made and first exhibited, I have rarely revisited something with the same material treatment to effect what is essentially a heightened version of an earlier state. That sort of ‘making good’, however satisfying it is for tying up loose ends, is just that, an end in itself.

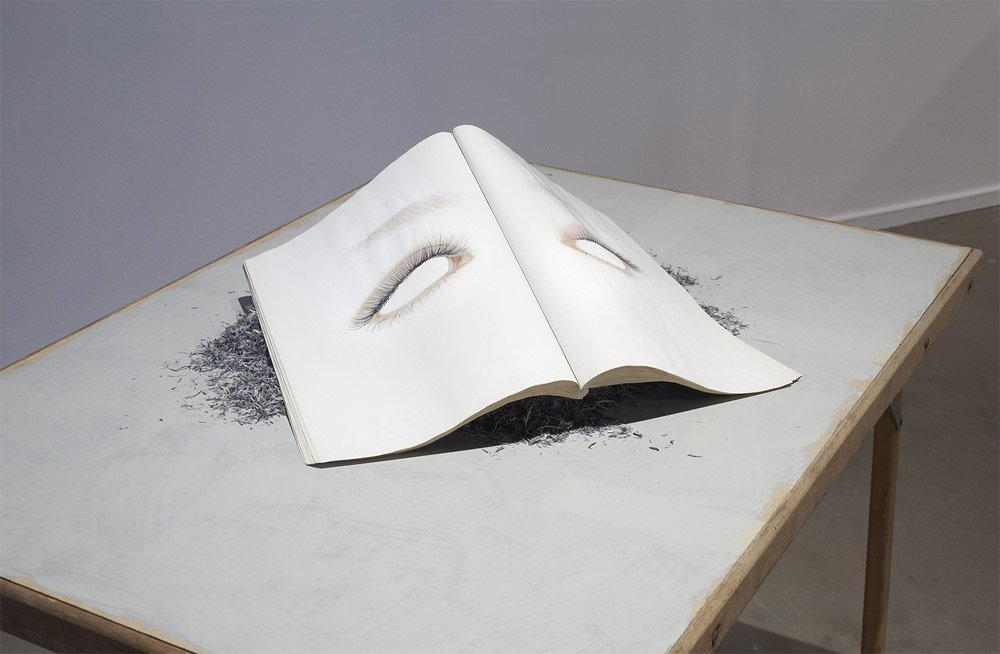

If something I am working on does not eventually mutate into something else that is either more vital or a more economical resolution, it will usually find itself abandoned. The erasure works (which mostly involved the removal of the printed image from pages of magazines with an eraser) stopped because I couldn’t physically bear to continue. Circumstance coupled with temperament certainly plays its part, as it did with a vacant bazaar (1999–2010), which kept going for over a decade because it could and because it had nowhere to go – no end point.

I do have a fascination with the resistant, slippery nature of the copy – with what happens in the transactions between a thing and its double, or its triple, between the thing and its translated states. Working in a serial way, utilising the distinctive counting and unfolding in time and across space that succession and iteration entail, certainly comes into play with the copy and the multiple, as do internal repetition and difference, symmetry and dissymmetry.

For instance, there exists an unseen version of SLAVE. It is exactly the same footage with exactly the same temporal relationship between the films in the installation, but the whole thing is refilmed at a slant. And because the surface it is screening on when it is filmed is particularly intolerant of any departure from an ideal viewing position, this slanted take opens up the original state of SLAVE (itself a copy) in a surprising, charged and revealing way. Perhaps this is close to what Francesco Stocchi means?

If I return again and again to an image or a form, or, even, to a specific location to film the same scene year in, year out, as with Epping Lock (2014– ), and if it is not to test those elements’ resilience – or mine – it is in the hope of finding there a share of that elusive elsewhere that is both theirs and mine.

MK: Your process involves complex loops and interplays between technology and manual touch, rigour and chance. Can you speak a little bit about these factors?

CC: The appeal of pictures in a glossy magazine is as much how they feel at your fingertips as how they appear or what they show. Images on a computer screen look back at us under the constant threat of displacement and revisal by choice, metrics, chance or system error. Shooting only the thirteenth frame on a roll of film made for twelve; feelings of inadequacy, redundancy or boredom when following the correct protocols or appropriate uses of dumb mechanical tools and smart devices – these are but a few instances where paying attention to quite different orders of testimony, as if they mattered to what might be apprehended or communicated, has been instructive.

As I alluded to in my dealings with the Flavin ‘monuments’, something crosses your path and you embrace it (or possibly take a swing at it). If you are agile and lucky, it is thrown off guard and unbalanced by the contact; and in that moment, you detect an opportunity worth pursuing. Then, with everything you can get your hands on, that you are given, you take licence with it, dislocate it, to open up a space of autonomy, however small or provisional.

A thought that’s been with me recently is: if we are no longer in the era of reproduction, as Harun Farocki thought, but in one of construction, how does the lassitude of that earlier technological order manifest itself today in our images and image systems, or haunt our imaginaries?

MK: What are you working on at the moment? I’m interested to hear about recent or emergent developments in your practice.

CC: Or, what’s not happening in the interruption? With wandering a proscribed activity these days, the appeal of the street filming (A Man Held, Centre for Contemporary Photography, 2015), which has been my most-days activity over recent years, has evaporated. Even when it was possible, the pleasure of walking and waiting, of watching, waiting and walking this city, was so troubled by other thoughts that I struggled to connect with its altered rhythms. A decline in patience during this closed winter certainly hasn’t helped.

I do keep in touch with my Disport workmates** (Two Shores, ReadingRoom, 2019) who, like downed tools everywhere, are in their element these days – taking their chance in the quiet to try out new functions and postures. **(photographic tripods)

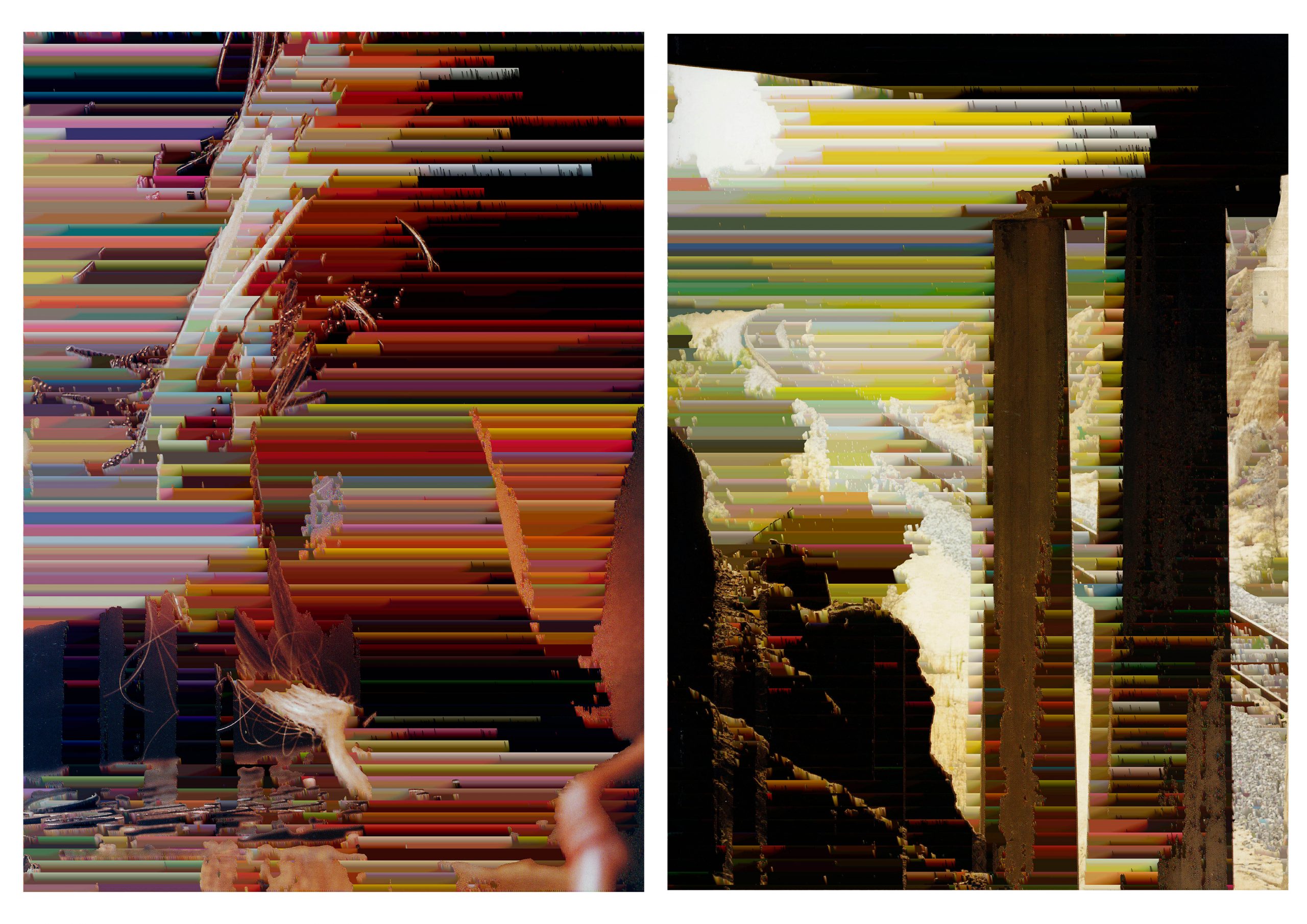

Otherwise, I am making scanner-interpolated photo works. These enclasticines echo the photographs that I was making in the late 1980s, specifically with regards to their distinctively hybrid picture matter and dual temporalities and their co-opting of chance and the vagaries of technological processing. They also follow the approach of the ICEdust series (Milani Gallery, 2016) and share something of those works’ chimeric digital-analogue structure. Images are again borrowed, but this time taken from a wider range of sources, including reportage, and having a different set of misapplied algorithms trained on them. The result is a visual terrain with a notably elevated technological temperature. There’s a shift in the scene-making too, towards something more spatially complex and, dare I say, theatrical. With this new series, I am also thinking more than ever about ensembles of pictures and their interrelations.

If in the doubt and anxiety of the pandemic containment, and in the surging wine of idleness that has accompanied it, anything redeeming has gestated, it has been in the shape of black paper serviettes misshapen nightly, unheedingly, over dinner; mindfilms of crowd scenes and tightly packed irreverent bodies in now-empty public spaces, once-local places that are presently out of reach (with Bay 13 figuring prominently); and, for its joyfully liberating implications, a professional practice of unfaithful art documentation that, echoing Smithson’s photographer, destroys appearances with each click of the camera!

Christian Capurro is represented by Milani Gallery, Brisbane

christiancapurro.com

making and unmaking conversation with Danny Lacy, Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery in 2018

SLAVE. Interview at ACCA 2014

Milani Gallery, artist page

TarraWarra Biennial 2021: Slow Moving Waters

Two Shores, ReadingRoom 2019

Monash University Museum of Art – Collection

Harun Farocki (1944–2014), or Dialectics in Images

Image captions

Portrait photograph by Elizabeth Brown

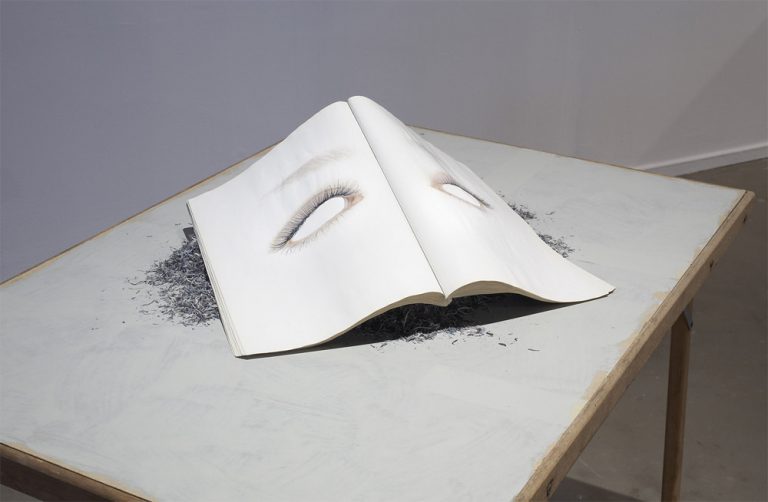

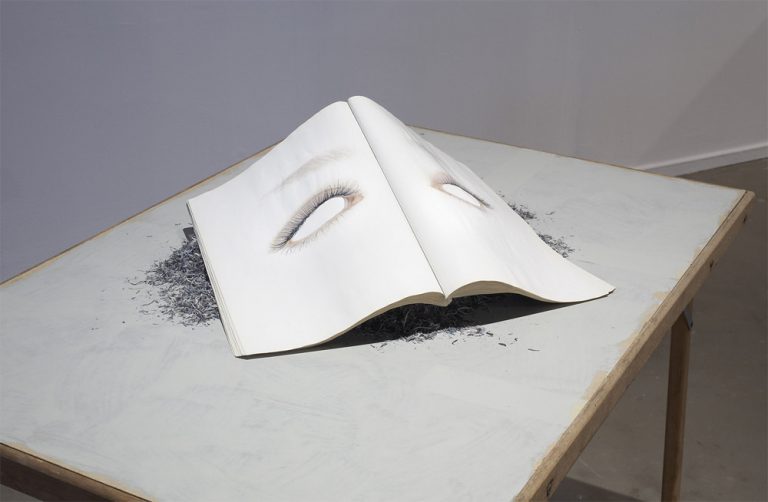

Christian Capurro, a vacant bazaar (provisional legend) 1999–2010, installation view, Artspace, Sydney, 2010

Christian Capurro, SLAVE, 8-channel digital video installation, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, 2014

Christian Capurro, A Man Held, installation view, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, 2015

Christian Capurro, Two Shores (Act 2), installation view, ReadingRoom, Melbourne, 2019

Christian Capurro, Two Shores (Act 1), installation view, ReadingRoom, Melbourne, 2019

Christian Capurro, Deluge (after JB) 1999/2001, C-Type photograph, Collection of the Art Gallery of Western Australia

Christian Capurro, enclasticine (410) 2020, inkjet print, Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane

Christian Capurro, enclasticine (217) 2018, inkjet print, Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane